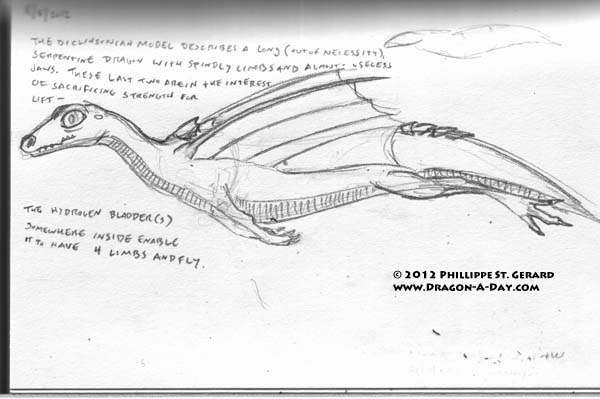

So with the intent of pursuing the Dickinsonian model a bit further, I started idly wondering about swim bladders, which Dickinson likens the hydrogen storage chamber(s) to. (At one point he describes dragons as swimming through the sky on modified ribs ala Draco volans, which he makes a point of mentioning, even though the Internet was only going crazy about the little dragons a few months back.)

However, since the Dickensonian dragon is long and serpentine (out of necessity, according to the physics he presents and the references he draws from to establish his claims) , it would seem (to me anyway) that the closest existing natural-world analog would be an eel or other long-bodied fish.I’m also having a hard time wrapping my head around the idea of the dragon digesting its own bone structure. Limestone seems like a much better source of calcium, because if nothing else, the dragon would have to replace the minerals it burns at such a rapid rate.

However, I haven’t been able to find a useful visual of an eel’s internal anatomy, aside from lots and lots of things about parasites that (interestingly enough) inhabit the swim bladders of eels and other fishes, and I was actually thinking of doing some sort of internal anatomy sketching, but it appears that I’ve been stymied for now at least.

So, for now, here is some external anatomy, based on what I know, though I’m not sure how to apply it- it seems like the tail would be too heavy to keep if we’re going from a strictly evolutionary approach, unless it was somehow involved in steering.

It’s probably also important to note that I haven’t finished rereading Flight of Dragons yet, especially the later chapters where he talks more about external anatomy.